To date, towers have not been subject to heavy regulation but a number of factors including the growing prominence of an independent tower industry and the introduction of 5G networks requiring massive densification are driving regulatory discussions increasingly into the spotlight. Delta Partners examine the current tower regulatory landscape and discuss how regulation should evolve to support the betterment of the communications sector.

1. Context

Telecoms is an industry where economic regulation is a critical factor that determines growth, profitability of investment, affordability for end users and incentives to innovate. Typical regulatory measures include licensing, price regulation at retail and wholesale levels, reference offers, non-discrimination and even mandatory separation of different asset classes. However, the towers layer has not been subject to heavy regulation:

- Operators usually deployed duplicating infrastructure, so none could abuse its dominance in the infrastructure space to gain advantage in the retail market;

- Densities of macro grids remained fairly stable from 2G to 4G as all these technologies predominantly used low- to mid-band spectrum bands for coverage purposes. Even with traffic growth and capacity driven densifications, additional sites did not increase the grid size by more than 20-30%.

Under these conditions, regulation of infrastructure was mostly focused on ensuring site aesthetics, environment protection and, more recently, promoting collocation.

However, two important trends could encourage the need for a greater regulatory oversight:

- The emergence of a new breed of infrastructure-only players who drive consolidation of infrastructure assets;

- The introduction of 5G networks that use high and ultra-high spectrum bands, resulting in massive densification of networks with deployment of small cells.

In this context, market players should drive regulatory agendas to ensure there’s enough scrutiny over any sign of market abuse, promote infrastructure sharing and support industry players in removing any legal and regulatory obstacles for large scale site deployment.

This Delta Perspective shares the key trends that may influence industry’s response to the regulation of infrastructure, explains current practices of infrastructure regulation across developed and emerging markets and proposes new directions in regulatory agendas to support the required network densification.

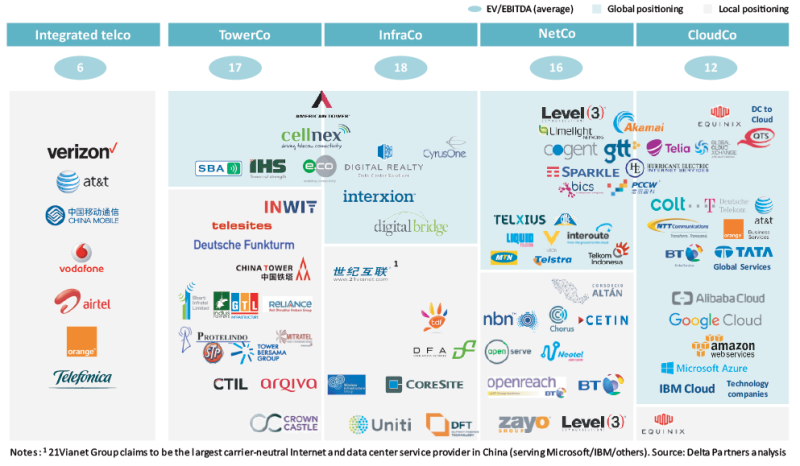

Exhibit 1 – Infrastructure players overview

2. Key trends that could drive the need to shift regulatory frameworks

2.1. New breed of infra players

Over the past decade, the telecom industry has seen the emergence of a new breed of infrastructure player. They are focused purely on deploying, operating and maintaining telecom infrastructure to telecom operators. The most widely well-known and adopted model are TowerCos, but there is growing number of those who are focused on pure infrastructure or basic wholesale connectivity services. These include: InfraCos and NetCos. Ownership and control over these new entities could range from completely independent pure-infra play through full or partial ownership by one or more telecom operators to light form of cooperation between telcos to share deployment or utilization of certain infrastructure elements.

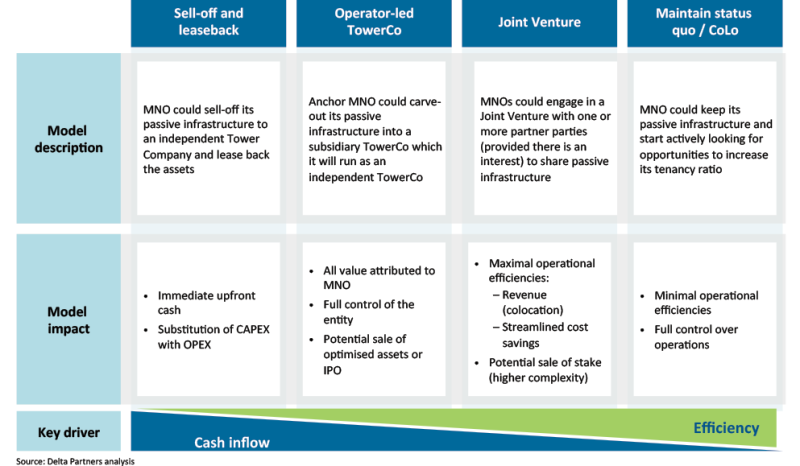

The emergence of new business models has played an important role in generating efficiencies in the sector through better utilization of assets, deleveraging balance sheets and allowing telecom operators to focus on innovation and quality of service. However, the majority of infrastructure players were created through the carve-out and sale of the existing infrastructure from vertically integrated operators – including heavily regulated entities. As a consequence, one of the critical elements in telecom value chain, fundamental to the provisioning of connectivity services, moved away from traditional telecom regulation.

Yet, since the underlying assumption of all new business models is sharing assets by several telecom operators, it inevitably leads to infrastructure consolidation and lower redundancy. This causes heavy reliance on the financial health, operational capability and fair treatment of all players by a limited number of strong Infrastructure operators and, as such, could lead to greater regulatory scrutiny from a range of regulators such as telecom regulators, policy makers, competition authorities and municipalities among others.

Exhibit 2 – Infrastructure ownership and control options - Tower infrastructure example

2.2. 5G introduction and small cells deployment

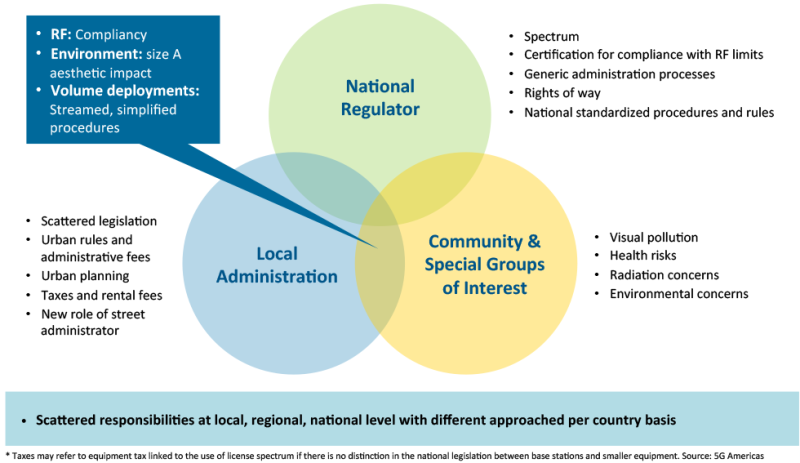

With 5G’s introduction, operators are expected to deploy at least 10 times the number of outdoor urban cells currently operated with 4G. With such a massive scale deployment, specific challenges will arise which could severely impact site deployment time. These challenges include obtaining all required permits for site deployment, obtaining rights-of-way to provide fibre backhaul, conforming to each city’s aesthetic and environmental regulations. Since all these processes and approvals are managed by multiple institutions on country and local level, the administrative burden can greatly impact the pace of large-scale site densification and fiberization required for 5G networks. According to a study conducted for 5G Americas, the primary challenges include:

- Fragmented regulatory frameworks at national and local level, preventing a scalable deployment process;

- Local authorities can delay or forbid deployments for aesthetic, environmental or public health concerns but these rules are inconsistent city to city;

- No standardized approval for equipment and sites. Only a few countries have a WiFi-like ‘fast track’ approval, or exemption, for small cells which conform to certain requirements (e.g. size, power);

- Inconsistent fees for use of public infrastructure that sometimes are so high they can break the business case for small cells in a particular city;

- Backhaul and approval issues could cause an operator to postpone the start of a densification project, especially an outdoor one, by an average of 26 months.

Another factor impacting infrastructure is the increased power of real estate owners. Until recently, operators and TowerCos depended on property owners to deploy rooftop sites. With the increased need for indoor sites and small- cell deployment, real estate owners will become de facto local monopolies. Regulators should consider how to avoid situations where these new players in the telco value chain extract abnormal returns and limit the availability and quality of 5G.

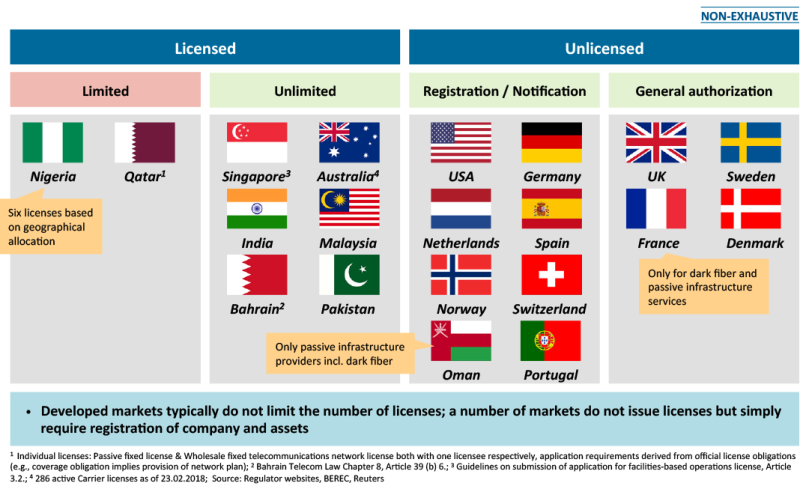

Exhibit 3 – Regulatory barriers to entry in developed markets are typically low

3. Current state of infrastructure regulation around the world

Although infrastructure sharing lowers CAPEX requirements in the telecom sector, promotes investment in QoS and leads innovation in the regulatory agenda globally, tower regulation is in its infancy. Yet, even with the relatively small sample size of countries where some form of tower regulation exists, we already see differing approaches between developed and developing markets with greater regulatory oversight and ex-ante regulations for the latter, especially for licensing and capital requirements.

3.1. “Light” form of infrastructure regulation in developed markets:

Markets like the US and Western Europe typically require no more than a registration/ notification with relevant regulatory bodies. Some countries, such as the UK, Sweden and Denmark, have issued a general authorization allowing any registered company to engage in TowerCo/InfraCo services.

In the US, there are certain restrictions for TowerCos:

- Foreign ownership is limited to 25% - although this can be waived - likely because of US concerns regarding national security and security of critical infrastructure;

- New site deployments are subject to zoning laws;

- TowerCos are treated as real estate companies and generally operate as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT), which are subject to certain legislation in taxation and dividend payouts.

While TowerCo regulation in developed economies is ‘light’, regulators have introduced legislation that encourages or even enforces the sharing of communications infrastructure. The main driver for the regulatory push towards greater collaboration is efficiency of investment but also the protection of natural environment and health and, finally, aesthetics. The design standards to ensure aesthetic rules and environment and health protection rules may vary between different administrative units in the same country, as it does in the UK or US. This increases the complexity and costs of regulatory compliance as well as time required for large scale deployment of new sites.

Regulation comes in the form of site sharing rules, defining target designs of new sites to accommodate additional tenants and maintaining centralized records of sites to avoid redundant deployments.

The requirement to provide information regarding existing infrastructure portfolio can be found in emerging and western markets. The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) runs the Antenna Structure Registration (ASR) program which imposes regulation upon the owners of antenna structures to register with the FCC. Those affected include Antenna that are higher than 200 feet above ground level or those that could interfere with the flight path of a nearby airport. Germany’s Federal Network Agency “Bundesnetzagentur” operates the “Infrastructure Atlas” which contains detailed information from 650 infrastructure owners on the availability of fiber optic cables, ducts, masts and base stations. The provision of data, initially voluntary, is now mandatory.

Sharing regulation can be broadly categorized across three “axes”: the breadth of its applicability across different components of communications infrastructure; its applicability to new deployments and/or existing infrastructure; and whether it is applied asymmetrically (to dominant providers only) or symmetrically (to all providers):

- For new deployments, regulators typically require a certain level of coordination between market participants to reduce duplication of infrastructure. These coordination requirements can be sector- specific (telco only, like in Spain, the Netherlands and the UK). The Dutch telecom act requires coordination on the deployment of passive infrastructure such as ducts, manholes and sites for mobile antennae (e.g. towers). However, current EU guidelines advise legislators to enforce coordination on a cross-sector level including telecom and utility companies (e.g. joint duct deployment for fiber of utility and telecom companies as well as joint usage of manholes);

- Sharing regulation for existing infrastructure is mostly focused on ensuring competition and enforces access rules for passive infrastructure such as ducts and dark fibre but also for two or three active wholesale products from operators;

- Access rules have traditionally focused on dominant market players with significant market power (SMP). In countries like the US, Spain, Singapore and the Netherlands, this has been extended to apply “symmetrically” to all market participants.

Exhibit 4 – Infrastructure regulation in developed markets is focused on incentivizing competition through accessibility

3.2. Regulation of infrastructure players in emerging markets focused on controlling asset ownership

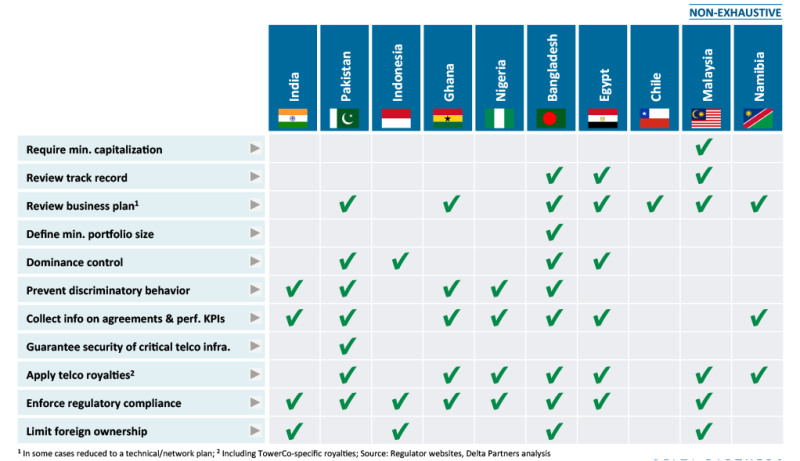

Compared with developed markets, emerging economies impose greater regulatory scrutiny on TowerCos. Sometimes these regulatory measures are enforced as conditions of a license, which must be purchased in order to offer TowerCo/ InfraCo services.

Such countries include Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Singapore, India, Bahrain, Australia, Nigeria and Qatar. The most stringent are Qatar and Nigeria where the number of licenses and, thus, the level of competition is limited. The scope of such licenses commonly includes the operation and lease of towers, ducts and dark fiber. Sometimes however, the scope of services may be much wider including services such as satellite hubs or submarine cables like in Pakistan and Malaysia. Other than licensing, some of the additional regulatory measures that are commonplace in emerging markets include:

- Capitalization requirements, which is typified by Malyasia, can also apply to companies in western economies depending on how they are incorporated. For example, US stock exchange listed companies need to have a minimum aggregate market value of publicly held shares of $40 million domestically and $100 million internationally;

- Requirements for relevant experience and expertise which are subject to regulatory review. This occurs in Bangladesh, Egypt and Malaysia;

- Regulatory review of a business plan, as is the case in Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Egypt;

- Prevention of anti-competitive behavior and structures either through explicit license conditions or through reference to overarching competition rules;

- Master-lease agreements and technical KPIs. This is comparable to a reference offer for wholesale telecom services, requiring the licensee to specify terms & conditions of its services, such as the price it will charge to telecom service providers, which is common in India, Nigeria and Egypt;

- Countries impose limits on foreign ownership to ensure control and security of “critical infrastructure” (e.g. India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Malaysia). Limitations may range from a complete ban of foreign companies, which happens in Malaysia, to India’s approach of having a 49% minority stake limitation with the possibility of a waiver;

- License fees and royalties, which usually consist of a fixed initial and recurring fee plus revenue share ranging for 0.5% to 6.5% of annual gross revenue. Pakistan, Nigeria, Egypt, Malaysia and Bangladesh are notable examples of this.

The greater emphasis on preselecting the right number of potential entities that are focused on providing shared infrastructure in emerging markets may be driven by lower access to capital compared to developed markets. As such, the financial stability of the infrastructure provider becomes a critical factor for the sustainable development of the whole industry. At the same time, limitations on foreign ownership protect from a scenario of losing the control over critical assets to foreign entities.

Exhibit 5 – Tower regulation / licensing in emerging markets

4. What needs to change in 5G era?

4.1. Price regulation may be required for small cells

With further consolidation of the infrastructure layer expected, there may be growing concern over potential abuse of market power and overcharging telecom operators and, as such, squeezing their margins or inflating prices for end-users. Price regulation in the telecom industry was among the most commonly used measures to ensure that entities with SMP did not overcharge other industry players or end-users. Therefore, it’s valid to question whether price control mechanisms should also be commonly used to regulate prices for a pure infrastructure play. However, experience so far suggests that such a measure may not be required as market mechanisms appear to work well, at least for macro grid:

- Wholesale focus - Price regulation of telecom services mostly applies to vertically integrated players to prevent predatory pricing of wholesale services and to protect market position in retail market. Conversely, infrastructure players are purely focused on wholesale market and providing services to telecom operators;

- Price of services linked to price paid for the infrastructure - Majority of the infrastructure players, especially TowerCos and InfraCos, start their operations in a market through the acquisition of an existing portfolio of assets from existing telecom players. Occasionally, operators carve-out the infrastructure into a separate, fully or partially owned entity and procure services from them. In both cases the lease price for infrastructure reflects not only operational costs incurred by infrastructure player but also the agreed value of assets acquired (e.g. portfolio of towers). This transaction value is determined by numerous factors, including the owner’s cash requirements. Price regulation would therefore impact valuation of assets and as such could reduce interests of buyers and sellers to enter in transaction;

- Cost-plus vs cost-minus approach - The common approach to price setting for regulated services assumes that the price of a service should be close to self-provisioning costs and assumes a margin guaranteeing fair return for service provider. In infrastructure plays, the actual market price for services offered by infrastructure owner assumes improved utilisation of shared infrastructure and, as such, should be lower than self- provisioning costs.

Price regulation is unnecessary for the macro grid. Yet, a certain influence over price setting may be required to prevent abuse of power by landlords and municipalities. With extremely dense small cell networks, the locations for both outdoor and indoor sites become critical for rollout and are very valuable. This creates a risk of setting rental prices above the fair value. Regulatory measures that could prevent inflation of rental prices range from restricting rental charges for the telecom space to zero-rental fees for small cells. For indoor sites, sharing of small cells should be encouraged with price guidelines recommended by regulators.

Exhibit 6 – Regulatory and administrative fragmentation for site approvals (example for the US)

4.2. Importance of regulation in streamlining 5G deployment process

As network deployment shifts from low to mid band technologies (3G/4G) to the high-band, super densified 5G technology, traditional regulatory frameworks and processes may pose a significant obstacle to large-scale and economically viable technology upgrades.

As 5G site deployments are expected to grow ten-fold compared to existing technologies, it is paramount that deployments are swift and cost efficient. While certain steps of the deployment and activation process depend on operators themselves (e.g. radio planning, installation and backhaul connection), it is administrative and regulatory processes that cause the vast majority of deployment time for telecom sites. Even though some operators claim they can deploy and activate a small cell within a day, getting relevant approvals and negotiating fees may take up to two years, like in the US. This illustrates the disproportionate effort and time operators have to invest in administrative tasks to deploy their networks. This administrative burden might have been manageable in a 3G/4G scenario where large macro sites could serve larger numbers of customers and could be deployed at a slower pace. Yet, considering that 5G networks will depend on small cells, which connect a significantly lower number of customers, it is clear that administrative timeline needs to decrease if 5G deployment is to be an economically viable investment. Some of the main regulatory and administrative challenges that need to be tackled include:

- Regulatory and administrative fragmentation for site approvals - In some countries (e.g. US) gathering the required approvals for a single site or small cell and related equipment may require a given operator or InfraCo to interact with several regulatory authorities and stakeholders at a local and national level. Under current regulation, most telecom sites, even small cells, have to go through the same approval process and considering the significant increase in deployments for 5G networks, current processes could easily compromise the cost and scalability of 5G networks;

- New site types - While 3G and 4G deployments are largely made up of traditional telecom towers and rooftop sites, 5G deployment will be dominated by smaller set ups such as small cell solutions on electrical utility poles or street light poles. Current regulatory and administrative frameworks for telecom sites need to be updated to accommodate the efficient deployment of such new site types;

- Access to existing power sources - Due to the larger number of sites in a 5G network, there may be a shortage of space for dedicated new power sources for a significant number of small cells. Tapping into existing power sources provides challenges from an administrative and cost perspective as access must be negotiated with municipalities and/ or landlords. Regulators need to provide effective frameworks at which existing power sources (e.g. in existing buildings) can be accessed quickly and at a sustainable cost;

- Prevention of predatory rental charges - As operators and infrastructure players will be required to deploy large numbers of sites to launch 5G technology, they will be more exposed to predatory pricing of rental charges. Due to the smaller coverage radius of 5G high band sites, network planning and site acquisition teams will be much more limited in their flexibility to choose from several locations to accommodate their network design, consequently giving them less bargaining power when negotiating with landlords. Hence, regulators need to be wary of the effect that excessive rental charges could have on the business case of 5G networks.

Although there is much work to be done, some regulators have already taken steps to adapt regulatory and administrative processes to 5G requirements:

- In the US, 20 states have passed legislation aimed at easing the deployment of wireless infrastructure, much of which has been focused at formalizing shorter approval timelines and simplifying access rules for rights of way and city structures;

- Singapore’s IMDA has regulation to reduce the rental cost of telecom sites to zero. Under the new Code of Practice for Info Communication Facilities (COPIF) any new rental agreement for telecom sites will be free of charge.

Considering the large number of telecom sites needed to be deployed to build 5G networks, the main challenge from a regulatory perspective is to reduce the length and cost of administrative processes, approvals and fees. Current timelines and cost structures, if unaltered, could significantly slow down and limit the scale of 5G deployments.

5. Summary

The degree of tower regulation globally is limited. Regulators in developed markets are focused on aesthetics, environmental impact and promotion of infrastructure sharing, while those in emerging markets restrict the number of infrastructure players and ensure that only experienced entities with proper capabilities are licensed to operate telecom infrastructure.

While current regulation may have been manageable and appropriate given the scale and type of deployments in a 3G/4G era, upgrades to larger and denser 5G networks will require certain adjustments to facilitate an efficient and economically viable transition to 5G technology. Considering an expected ten-fold increase in the number of sites deployed to build 5G networks, regulators should initiate legislation to streamline approval processes and prevent excessive fees (e.g. rental charges or rights of way for fiber, indoor installations) for telecom sites. If operators and infrastructure players have to navigate through an environment of multi-year approval timelines and predatory rental charges, the cost efficiency and scalability of 5G networks could be compromised. To safely navigate regulation, Infrastructure players should build capabilities in areas of market regulation and start a dialogue with regulators to help drive a development of optimal regulatory environment to support large scale infrastructure deployments.

Regulators around the world need to think of ways to help TowerCos flourish in their market, whether that is mandating Telcos to carveout their assets or offering incentives for TowerCos to establish themselves and acquire local assets. In markets that are either too small or economically challenging, regulators need to be progressive enough to attract TowerCos by setting win-win market conditions, knowing that TowerCo’s help achieve ultimate goals of telco regulators, which is promoting universal, cheap and fast access to infrastructure.